Python Practice

This activity will guide you through learning the basics of Python. We strongly encourage you to follow through all of the steps, and only skip some if you already have Python programming experience. To receive full credit for this homework exercise you must:

- Read and think about the Common Pitfalls presented below (you can do this either before or after going over the intro to Python materials)

- Read or watch the materials below to learn basic Python programming

- Write a program to implement a basic Rock, Paper Scissors game.

- Complete a form which asks you to enter two Python questions you have or topics which you think would be interesting to discuss in our next lecture.

Deadline: Sunday 1/24 at 11:59PM

Table of Contents:

- Features and Pitfalls: a high level overview of Python and some key differences with Java

- Learning Python Basics: links to video and text tutorials to get started with the language

- Assignment Part 1: Rock, Paper, Scissors: programming assignment to complete once you know Python basics

- Assignment Part 2: Python Questions: ask us questions to take your understanding of Python deeper

- Submission Instructions: how to submit

Python: Features and Pitfalls

From Python.org’s Executive Summary:

Python is an interpreted, object-oriented, high-level programming language with dynamic semantics. Its high-level built in data structures, combined with dynamic typing and dynamic binding, make it very attractive for Rapid Application Development, as well as for use as a scripting or glue language to connect existing components together. Python’s simple, easy to learn syntax emphasizes readability and therefore reduces the cost of program maintenance. Python supports modules and packages, which encourages program modularity and code reuse…

Let’s break down a few of the key points here, plus cover some common pitfalls.

1. Python is an interpreted language. This means that you do not need to compile your Python code in the same way you would Java or C. This helps make it fast to use and encourages a quick edit-test-debug cycle.

This has a few important implications. Most obvious, it means that you will run your programs by simply issuing a command like python myapp.py. But another powerful feature is that you can also simply open a Python interpreter by running python and type in arbitrary code. Each time you hit enter, it will execute your statements. This can be very useful for quickly testing how a Python language feature works.

2. Python has dynamic typing and dynamic binding. These mean that unlike C/Java, with Python you never will explicitly specify the types of your variables. Python will automatically determine at runtime what type you are using, and a single variable can be dynamically rebound to different types depending on its value.

This feature is probably what makes Python most popular for being a quick and easy to use language – it eliminates a lot of code by simplifying how variables are declared. However, be wary! This is also one of the most common sources of bugs in Python code. Being free from type-checking may reduce the code you need to write, but you can still get errors or strange results.

The code below will crash during the third print statement. If you tried to do something similar in Java, you would have caught the error at compile time, possibly before releasing a buggy program.

# https://repl.it/@twood02/db-python-types

a = "hello "

b = "world"

c = "10"

d = 5

print(a + b)

print(a + c)

print(a + d)

3. Python is object-oriented. For this class you may not need to use Python’s supports for classes much, but you will interact with APIs that provide you with objects to call methods on and get data from.

Here’s an example of a Python Class. It is not so different from Java, but the self syntax can be a bit confusing since you need to remember to include it as the first argument for any class methods. You can think of it as a reference passed to methods of an object that refers back to the object itself (like the this keyword in Java). The __init__ function is the syntax for defining a class constructor. Using object methods and data fields looks just like Java, but be aware that everything is public!

# https://repl.it/@twood02/db-PersonClass

class Customer:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

p1 = Customer("Tim", 36)

# I realized after writing this that I was off by a few years...

print(p1.name + " is not " + str(p1.age))

4. Python supports modules and packages. Python has a wide range of built-in libraries, plus many more available which you can use. This will be important as we go further into the class because we will make use of popular libraries like the Flask web framework and packages for interacting with MySQL.

There are two common pitfalls when using libraries in Python. First, installing and managing library versions can be messy. This is exacerbated when you have multiple versions of Python on your computer (fairly common as noted below). The common solution to this is using Python Virtual Environments, which are covered in the helper videos.

A second point of confusion for new Python users is that there are several ways to import modules and the functions within them. Suppose you want to work with the constant pi defined in Python’s math package. All of these approaches are valid code:

# https://repl.it/@twood02/db-Imports

import math

print(math.pi)

from math import pi

print(pi)

from math import pi as iLuvPi

print(iLuvPi)

import math as myMath

print(myMath.pi)

In the first case, we say we want access to the full math library, which then allows us to reference the pi member within it. In the second, we only import the pi data member, allowing us to refer to it directly. The third case once again imports just pi, but it specifies a custom name for it. Finally, we can also rename a full library that we are importing. While the final approach may seem silly, it can be extremely useful since it lets you abstract away the specific library you are using. For example, two different database libraries (one for MySQL and one for SQLite) could both expose the same standard set of functions; you could then write a program that does import mysqlLib as DB or import sqliteLib as DB depending on the backend database, but the rest of your code would work the same by simply referring to DB.

5. Python had a major revision from version 2 to 3. While often language version changes only affect power users, this change was enough to break even

Hello Worldprograms!

The most striking change from Python 2 to 3 is that old versions of the language treated print as a special keyword, meaning you could write print "hello world" to display to screen. With Python 3 and beyond, print() is a function, and thus like all functions, requires parentheses. So the first (and sometimes only) step for converting code to Python 3 is to use statements like print("hello world").

Another unfortunate challenge caused by this change is that many computers will have multiple versions of python installed since they may have legacy Python 2 code which needs an older version of the interpreter to run. You can easily see what version of Python is on your computer by looking at the output when you start the interpreter:

$ python # run the python command in my terminal

WARNING: Python 2.7 is not recommended.

This version is included in macOS for compatibility with legacy software.

Future versions of macOS will not include Python 2.7.

Instead, it is recommended that you transition to using 'python3' from within Terminal.

Python 2.7.16 (default, Jun 5 2020, 22:59:21)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 11.0.3 (clang-1103.0.29.20) (-macos10.15-objc- on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

If you have multiple versions installed, you may need to run a command like python3 or python2 to specify which version you want:

$ python3 # try a different version

Python 3.7.7 (default, Mar 10 2020, 15:43:03)

[Clang 11.0.0 (clang-1100.0.33.17)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

In this class you should be using Python 3!

6. Indentation and punctuation matter! In Python you will not end your statements with semicolons, and more importantly, indentation has meaning and is used to define code blocks instead of

{}braces like in Java.

Properly indenting your code is always good practice, and Python forces you to do it carefully. That’s in some ways surprising given how lax the language is in other areas. With a little practice you will get used to it, and it means that Python code is usually fairly readable because correct code is by definition well formatted. The choice of spaces or tabs is up to you, but you must be consistent!

Learning Python Basics

There are many ways to learn Python. Here are two approaches. If you find other good resources, post on Slack in #python.

Track 1: For Visual Learners

One option is to take advantage of the free LinkedIn Learning account that you get through GW. I’ve found that LinkedIn Learning has a wide range of courses on popular CS technologies, and that the quality of the videos tends to be better than what you’ll find on sites like YouTube.

Note: To use LinkedIn Learning you will need a (free) account on LinkedIn, and you will need to associate it with your GW email address. I am not paid by LinkedIn.

I recommend you watch the Learning Python video series. Watching the first two chapters will take less than an hour and it will quickly get you going writing basic Python.

If you want deeper videos covering a wider range of topics, then watch the Python Essential Training video series. It has 4 hours of content and even introduces the basics of using databases in Python. In 1-2 hours you could get all of the basics and come back for the advanced stuff later.

There are dozens of other Python development courses available on the site and across the internet, but those two looked like the best value for your time to me.

An alternative set of good videos are available as part of Google’s Python Class, but I think they are less streamlined than the ones above.

Track 2: For Text Learners

For a really quick, somewhat poorly organized overview of Python and its differences from Java, print out this Cheat Sheet.

For a more detailed introduction to Python with references to how it differs form Java, check out Python for Java Programmers.

For Google’s thorough introduction to Python (minimal programming experience required), check Google’s Python Class. It has both text sections and video tutorials, designed for a two-day intensive class.

Assignment: Rock, Paper, Scissors

This assignment must be solved on your own and will be submitted through GitHub classrooms. Details below

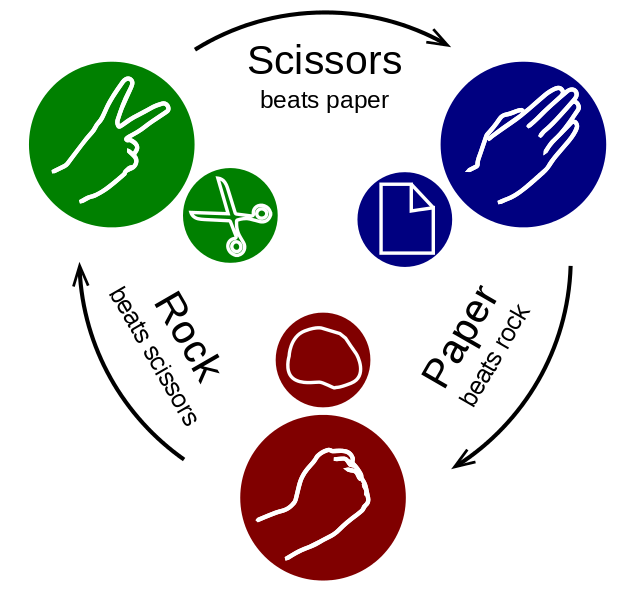

Rock, Paper, Scissors is a simultaneous, hand-based game, where only the luckiest (or wiliest) contestant will survive. Your challenge is to implement a much less physical (and much more predictable) text-based version of the game implemented in Python.

Rock, Paper, Scissors is a simultaneous, hand-based game, where only the luckiest (or wiliest) contestant will survive. Your challenge is to implement a much less physical (and much more predictable) text-based version of the game implemented in Python.

Our version of the game will assume that both players are positioned at the same keyboard, and rather than entering their moves simultaneously, they will take turns typing. Arguably this will reduce the tension and thrill of the game, but it fits better to our programming environment. If we play sometime, I’ll even let you go first!

We will be grading your submissions with an autograder, so it must meet the following criteria to pass our tests:

- Your program must be named

rps.py. - It should accept input from player 1 and then from player 2. The only acceptable input is one of the following key terms:

rock,paper,scissors. Other input should return an error and let the user enter again. - The final line that your program prints must exactly match the example below, i.e., follow the format

<WINNING PLAYER>'s <WINNING MOVE> beats <LOSING PLAYER>'s <LOSING MOVE>. Failure to precisely follow this syntax will get you a zero. - Any other output of your program will be ignored, so ensure that the final line has the correct result.

Here is an example run of a valid program:

Let's play rock, paper, scissors

Player 1's move?

rock

Player 2's move?

scissors

Player 1's rock beats Player 2's scissors

In the case of a tie, the final line should read:

Player 1 and Player 2 both played <MOVE>

Optional AI Extension: To push yourself further, you can extend your program to support a simple AI controlled opponent. Doing so will earn you your Week 2 engagement point. Randomly picking your move in RPS is generally considered the optimal strategy (although recent research suggests there are various ways to get an edge by exploiting human psychology). To complete this extension you must do the following:

- Add command line argument processing for your program. With no arguments it should function as above, but when run with a

-AIflag, it should enable AI mode for the second player. With a-AIAUTOflag it should enable AI for both players and not accept any user input. - An AI player should randomly select which move to make.

- When running in AI mode, the last line of your program’s output should be modified so it says “AI Player”, for example

AI Player 1's rock beats AI Player 2's scissorsif running inAIAUTOmode.

Assignment: Python Questions

While learning about Python and writing your RPS game, you must have had some questions about the language. Reflect on what you are still unclear about and fill out this form to specify what you would like to learn more about, or any valuable insights you want to share with your classmates. We will use these questions and comments to guide our future lecture on Python.

Completing this form will be combined with the coding above to determine your overall assignment grade.

Submission Instructions

Deadline: Sunday January 24, 11:59PM Eastern time

To submit your work, do the following:

- Make sure you have filled out the question form linked above

- Accept a GitHub classroom assignment using this link: https://classroom.github.com/a/PZVIIQeF

- Place your code in a

rps.pyfile in that repository - Be sure to commit and push your code, and verify it appears on the GitHub web interface

- Create an Issue in your repository titled “RPS HW Submission”. Put your full name and a link to your

rps.pyfile in the body of your issue - Be sure you followed all the above instructions carefully!

- If you are submitting late, be sure you carefully read the instructions in the Syllabus.